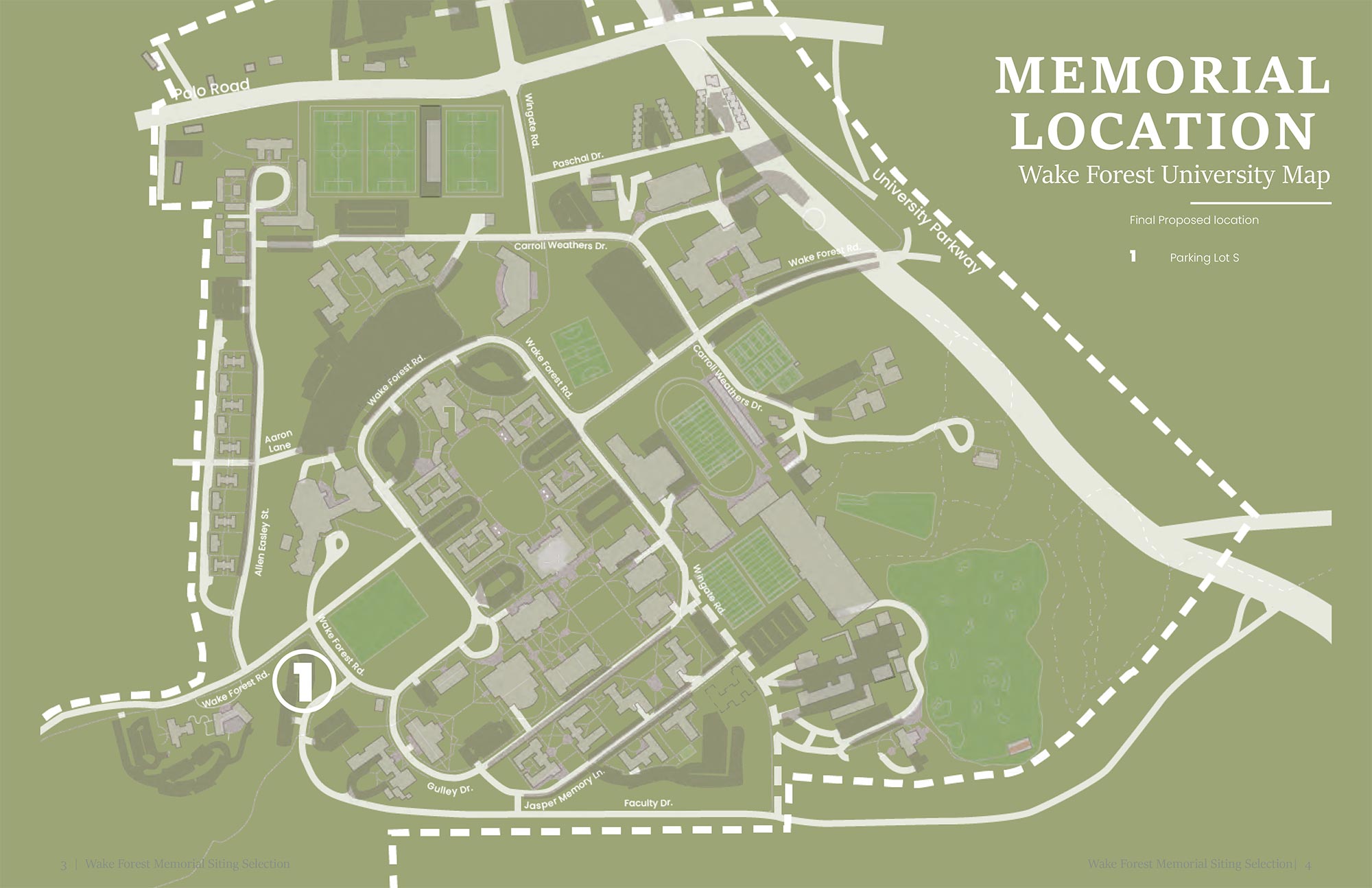

Committee Comments on Lot S

After a September 17, 2025 presentation by Baskervill of concepts on Lot S and a site on the Scales Lawn, as well as site visits with Baskervill designers on October 24, 2025, members of the Steering Committee overwhelmingly agreed that Lot S was the best location for the memorial amphitheater.

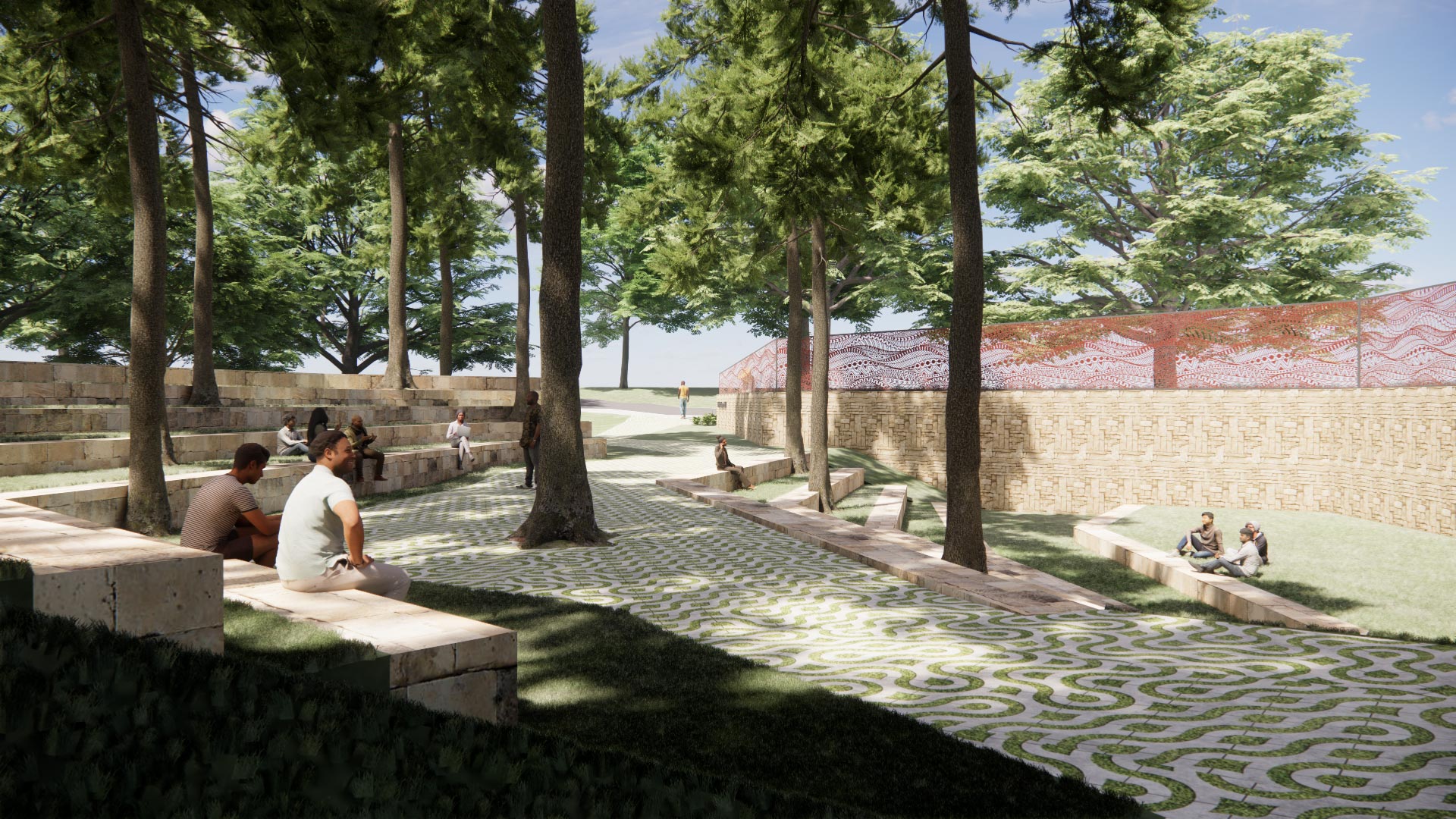

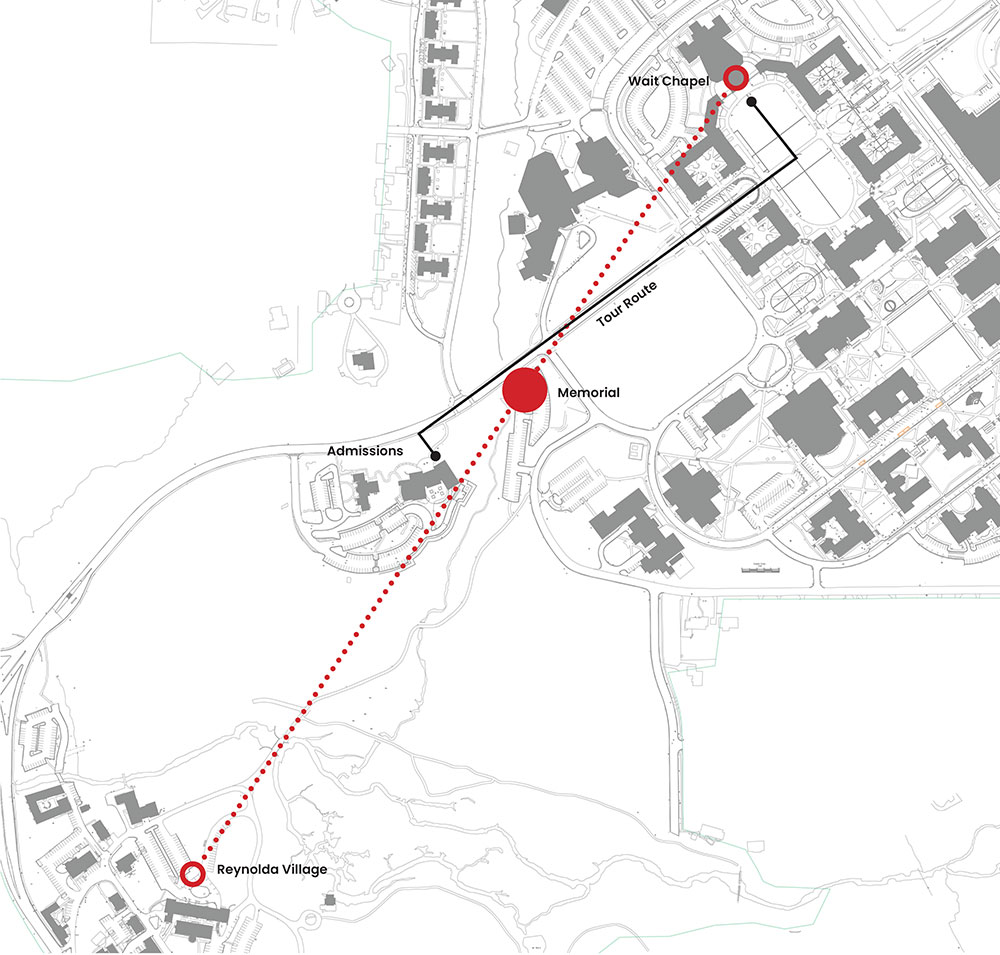

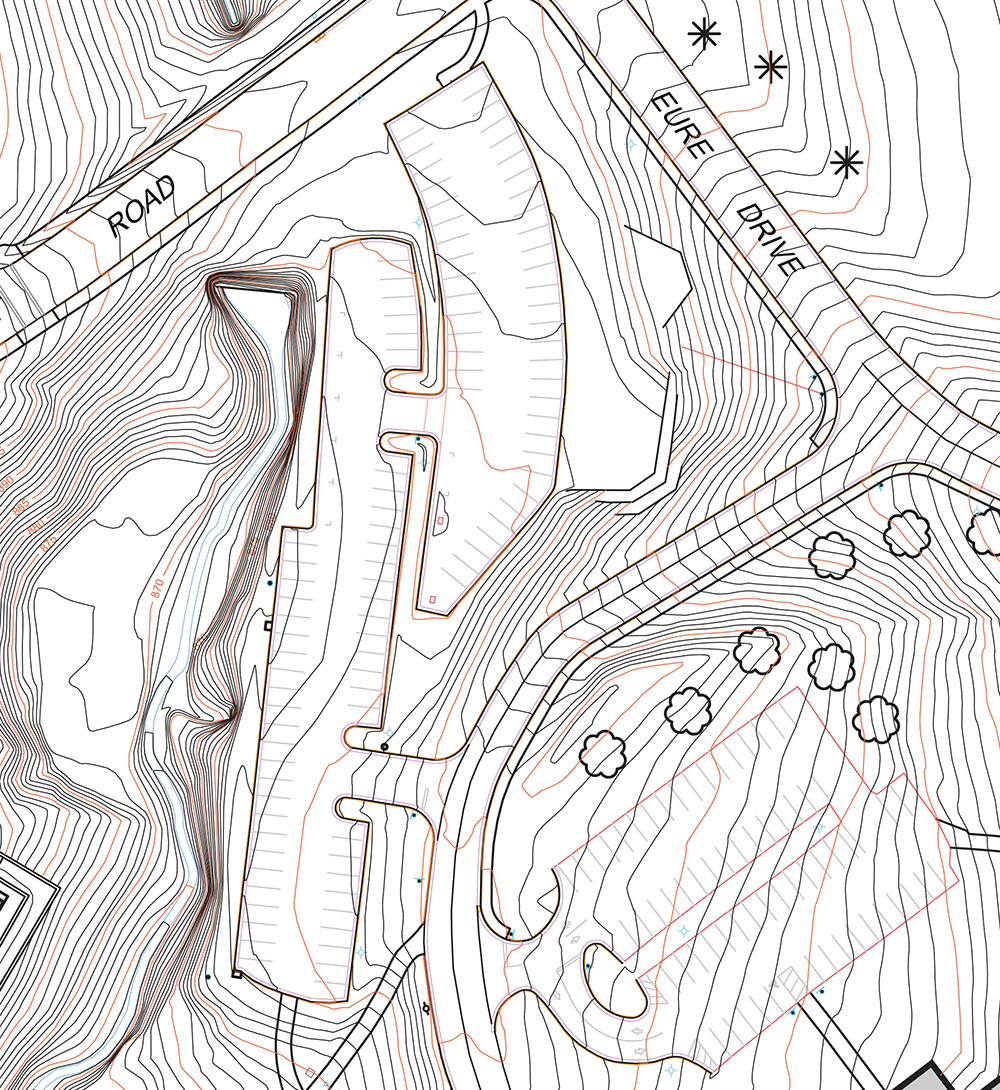

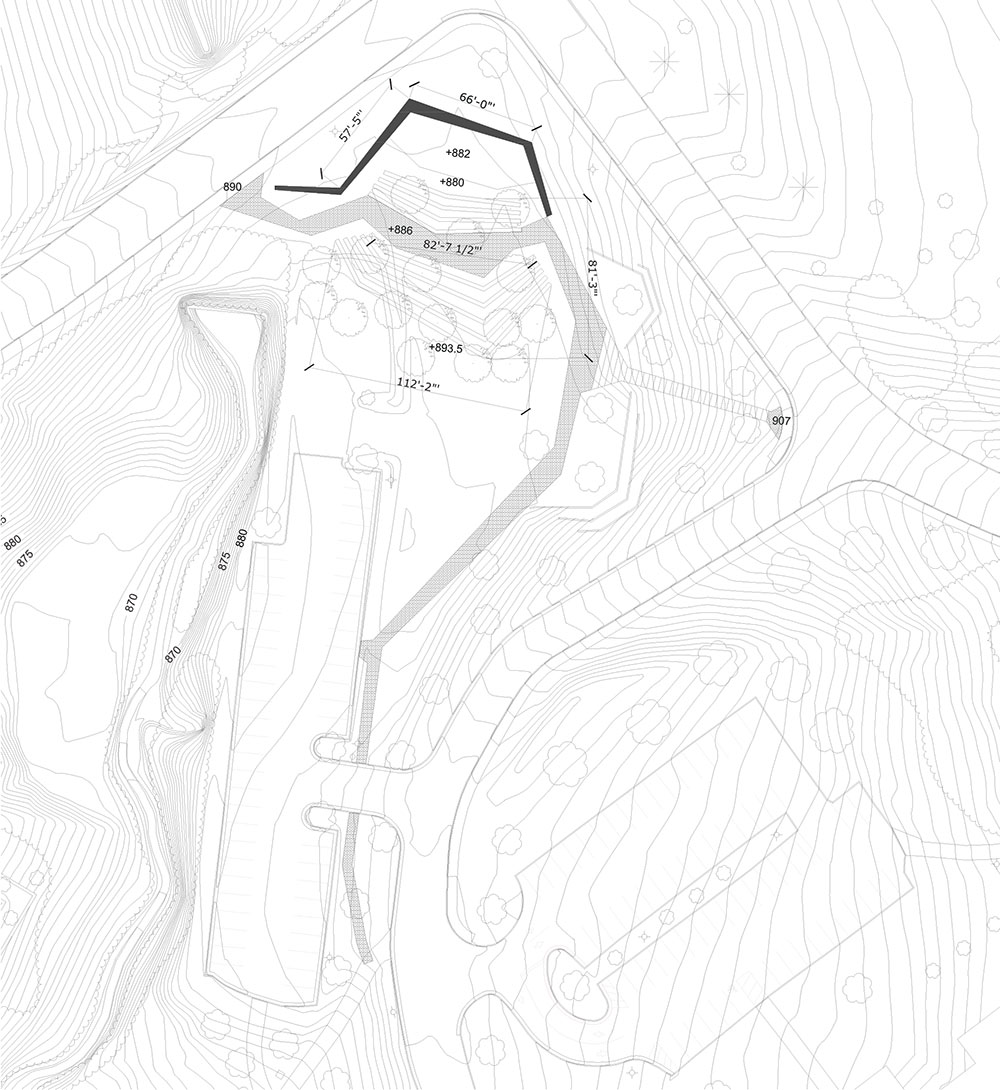

Committee members highlighted several qualities of Lot S, including its seclusion, intimate scale, and the existing tree canopy, as well as its strong sightline to Wait Chapel. The site’s proximity to the Visitor Center and the established student tour route was also seen as a major advantage. Members felt that Lot S balances a sense of discrete reflection with enough adjacency to student activity to avoid feeling too hidden— though some noted that this balance will need to be carefully managed through design.

The existing tree canopy and the connection to the Reynolda Trail were also seen as significant strengths. Members expressed that both the wooded landscape and the trail would become integral to the reflective experience of the memorial space.

“Special focused space away from everyday activity of the university.”

“Separate, shady, and quiet.”

“Real sense of peacefulness and spirituality”

“More solemn and promoting of reflection and thought. Beautiful trees nearby.”

“Visitors will walk past it from the Visitor’s Center”

“Feels safe and separate but also highly visible because it’s at the entry.”

“More likely to integrate the spot into my courses”

“A tranquil setting for reflection”

“It is its own distinct space yet not tucked too far away from general campus life.”

“A great natural sightline to the Wait Chapel steeple”

“Powerful addition to the campus tours, as one (if not the) starting point of the tour”

Between Origin and Outcome

From the Chapel to the Village

The story of Wake Forest is physically inscribed along a powerful linear axis stretching from Samuel Wait Chapel to Reynolda Village. At one end stands the Chapel, a symbol of institutional founding, intellectual pursuit, and the moral aspirations of the University. Yet beneath its brick and steeple lies a deeper, more complex origin story—one rooted in the labor, lives, and profits extracted from enslaved people. The early Wake Forest was funded, built, and sustained through the economy of slavery, and its founders—Samuel Wait among them—lived within and benefited from that system. The Chapel, then, while often read as a monument to faith and learning, also stands as an architectural witness to the University’s entanglement with enslavement.

At the other end, Reynolda Village occupies land once shaped by the Reynolds family—a space of agricultural production, wealth, and hierarchy. Like many Southern estates, its history is entwined with systems of labor, racial ordering, and power, even as it eventually transformed into a place of leisure, commerce, and gathering. Together, the Chapel and the Village form endpoints of a narrative spine—a physical line that begins in institutional founding and ends in reinterpreted land, where the built environment has outlived the structures of slavery but not the legacies it left behind.

The midpoint between them is not just a geographic center— it is a moral and historical fulcrum. Placing the memorial here interrupts the line of movement, asking all who pass between “origin” and “outcome” to pause. It is where past and present meet, where remembrance challenges erasure, and where the truth of enslavement becomes part of the daily lived experience of campus. The memorial’s location asserts that the story of Wake Forest cannot be traveled without acknowledgment—without seeing those whose forced labor and stolen lives made the journey possible.

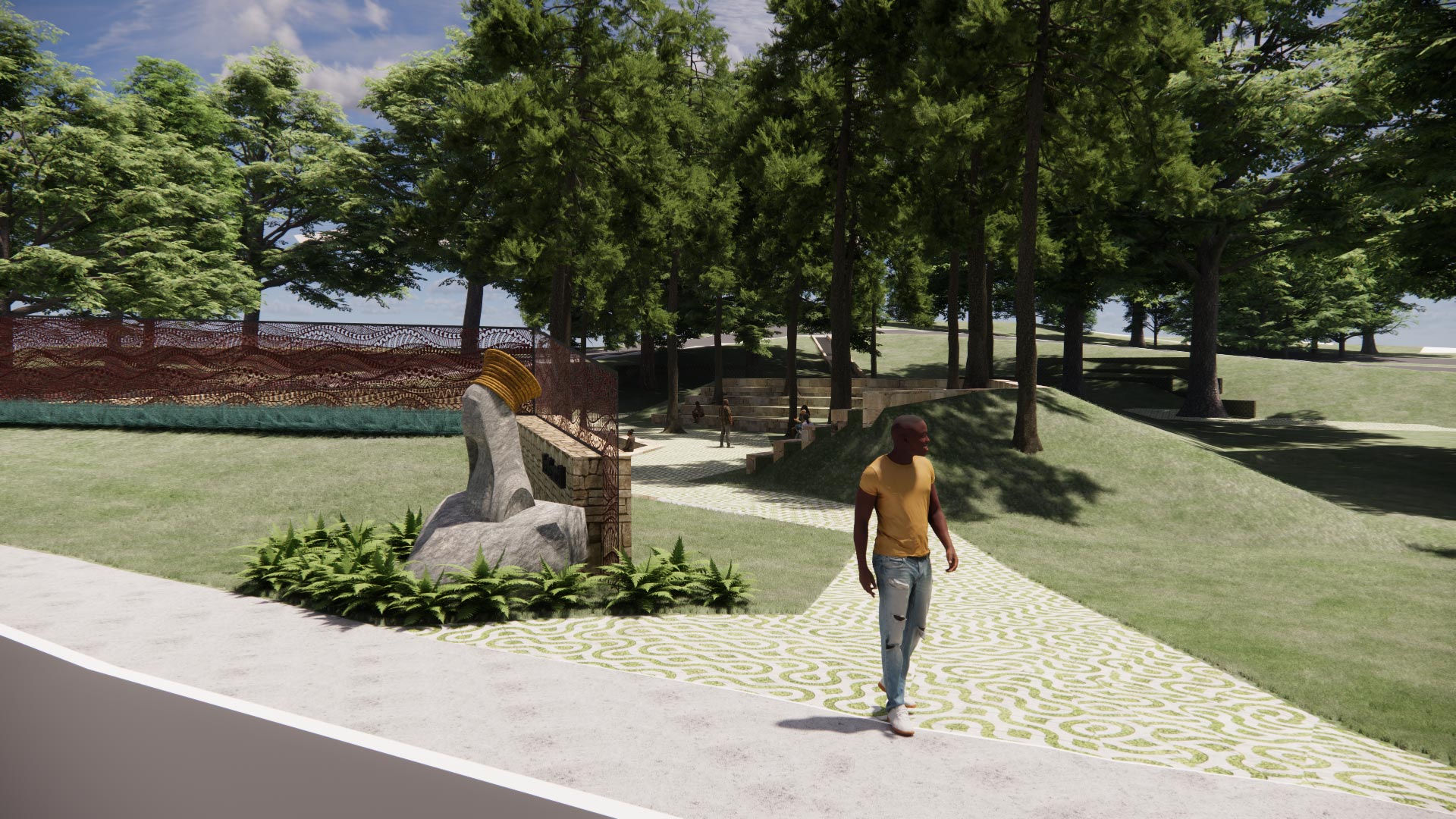

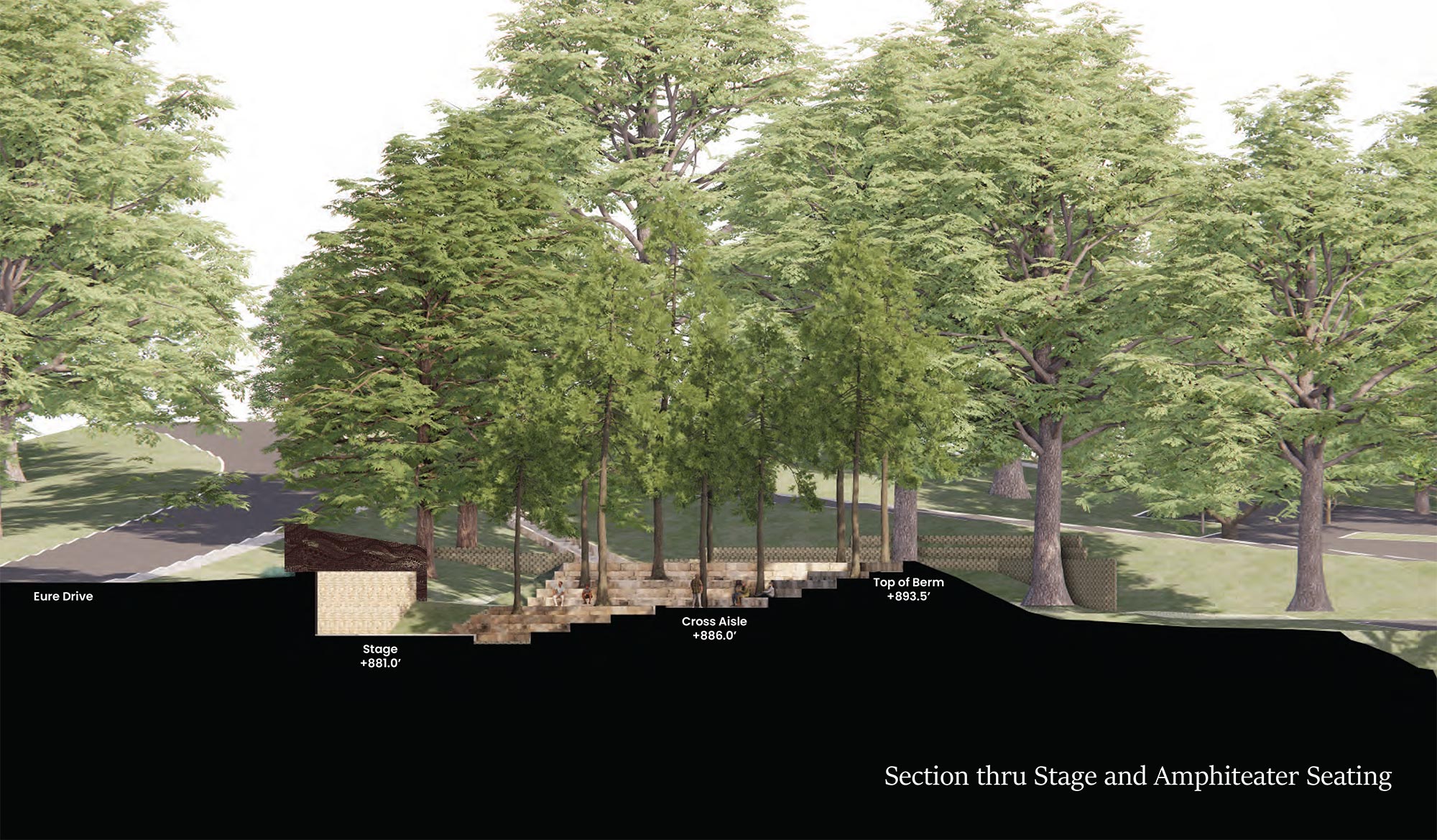

Plan Layout – Lot S

Existing

Proposed

Illustrative Plan – Lot S

Swarthmore College

Calloway Forest Preserve

Indigenous to the Southeastern United States, the Longleaf Pine holds deep historical and cultural significance in North Carolina. This tree played a central role in the early development of North Carolina. One of the eight species of pine recognized as the state tree, the lumber, shipbuilding, tar and turpentine manufacture, and interstate logging industries that it supported helped build the early wealth of North Carolina. The exploited labor of enslaved Africans and African Americans made the immense expansion in industry, a rise in regional and national political power, and economic growth possible in antebellum North Carolina.

View from Wake Forest Road